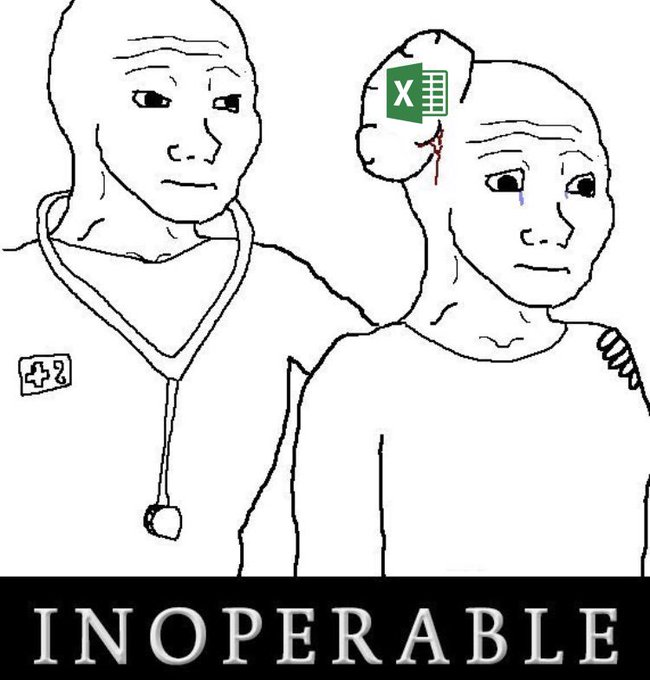

Spreadsheet Brain

“The inability to conceive of its own devastation will tend to be the blind spot of any culture." — Jonathan Lear in Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation.

“What is soul? I don’t know

Soul is the ring around your bathtub” — Funkadelic, What Is Soul?

(meme courtesy of Ashley Colby)

Ashley Colby, a US citizen, resides in Uruguay, lives a ‘Little House on the Pampa’ trad-wife lifestyle (it’s not LARPing if you do it for real), and crucially for this essay, is the coiner of the term ‘spreadsheet brain’.

She is also a Meme-Lord (Lady?) on Twitter, which is where I crossed paths with her. Politically she is probably well to the right of me. Such political categories lately seem more meaningless than ever though.

Thinking about ‘spreadsheet brain’, I realised that it has more than a little in common with Large Language Models, or a certain flavour of what is known as Artificial Intelligence.

When we hear that AI is going to take over the world and make humanity go extinct apart from a few specimens kept in cages for curiosity’s sake, do we consider that it is the most recent manifestation of what the psychologist and neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist would call ‘the servant usurping the master’, or, per Colby’s meme, ‘spreadsheet brain’?

I don’t believe AI is, or is going to become, sentient any time soon. The fact is that a system like ChatGPT has been designed to appear human when one interacts with it, and it is a major success on the part of the developers that they have achieved this. It’s something I never thought I would see in my lifetime. Yet the insistence that this amounts to sentience puts me in mind of this quote from Donna Haraway: “Our machines are disturbingly lively, and we ourselves frighteningly inert.”

ChatGPT and other recent Large Language Models are incredibly complex under the hood, but to simplify, they work by treating everything as language. Of course they can manipulate words like a human. They also categorise the elements which make up an image as if they are words. Objects, colour, context, artistic style, and so on.

AI breaks everything down, then skilfully puts it back together based on things it has been trained on (‘seen’) before. It works on probabilities, using a complex algorithm to work out what the next token (word, visual image, sound, etc.) is most likely to be within the context set for it by the prompter.

It’s one thing for an AI to be able to grasp sufficient meaning and order words into coherent responses. It’s another thing to think that implies the system is tantamount to being human. That itself is to reduce humanity to some kind of ‘wetware mechanism’. The proponents of the quasi-religious Kurzweilian ‘singularity’ would no doubt affirm that that is precisely what we are. But then they are terminally infected with Spreadsheet Brain.

So what is ‘spreadsheet brain’? We’ve all heard the Wilde quote about people who know the price of everything and the value of nothing. Well, that is it in a nutshell.

In a more technical sense, but still massively simplified, the left hemisphere of the brain is more concerned with quantity, with analysis. It breaks things down into parts and recombines them, yes, a bit like ChatGPT. The right hemisphere perceives wholes, quality, gestalts, contexts. McGilchrist often gives the example of a bird pecking grain off the floor. It uses the left hemisphere to select each individual grain. The right remains attentive to the world around it as a whole, including potential predators.

‘Spreadsheet brain’ is an imbalance in the hemispheres towards the left. This leads to an overemphasis on quantity over quality, on the part rather than the whole.

The metaphor is that the servant (the left brain) has usurped the master (the right brain). So we end up amassing endless things at the cost of destroying the biosphere (the context) in the process. The brain thus unbalanced develops a kind of arrogance whereby it imagines that doubling down on the way of thinking which caused the problem will somehow bring a solution. A more humble attitude would be to examine one’s core ways of thinking about the world.

There is nothing wrong at all with using the left hemisphere of the brain. Indeed unless we have had a severe stroke we cannot help but use it constantly. Yet our tools should serve us, not the other way around. For example, bureaucracy is a set of tools for managing agreements between people, yet often it seems that bureaucracy is created for its own sake. Anyone having had the slightest dealing with the Spanish legal system in their life knows this to the point of distraction.

The book ‘Seeing Like A State’, by James C. Scott contains many examples of this bureaucratic way of thinking, for example:

“The more uniform the forest, the greater the possibilities for centralized management; the routines that could be applied minimized the need for the discretion necessary in the management of diverse old-growth forests.”

As I implied above, the ecological crisis is a direct result of reductionist thinking. Ashley Colby would agree, I’m sure. She is dead against eco-modernists like George Monbiot:

“It is absolutely spreadsheet brain run amok among the Monbiot crowd, and in most mainstream journalism. They can only SEE what is MEASURED and then they try to extrapolate findings to the WHOLE WORLD and build management based on reductionism. It’s absolute madness.”

The dominating left hemisphere splits things up and then calculates their ‘value’ based on their separated parts.

The same way of thinking predominates in our present model of education. To allow children to follow their own in-built desire to learn is too chaotic to administer. Better (for the teachers and bureaucrats) to kill that desire. Then impose an extrinsic motivation based on fear of ‘not getting a job’, or ‘not getting into university’. Teachers who do not wish to operate within this model are pushed to the fringes.

The left brain reifies everything to make sense of it, yet we forget this is but a useful fiction. We even imagine that we ourselves are ‘things’, that we are ‘individuals’.

The concept of ‘the self-made man’ should be mocked whenever it appears. Yet it is held up as something we should all aspire to. Did this ‘Great Man’ make the Sun, the air, the water? Did he make everyone who has helped him become successful? To the ‘rational’ brain people are little more than ‘other things’ . Things which appear as more or less useful to the ends it is pursuing.

So, like many aspects of the reason-dominated mode of thinking, AI is useful and clever. Yet in its division of wholes into ‘parts’ and then recombination of them, it somehow seems to miss the most important essence. We may intuit this as we look at images produced using Midjourney or DALL-E.

I don’t want to dismiss all AI art, that would be spreadsheet brain in itself. A great deal of it does have value. Yet despite its undoubted technical mastery it can often appear as a ghost of art which was once alive. Maybe the missing essence is what we call ‘soul’, an indefinable quality which we know when we see it.

To those infected with spreadsheet brain, this is probably meaningless. If the images can be called beautiful, who cares how they are produced? Everything is content, in the final analysis, whether it’s a centuries-old woodcut or an upscaled Midjourney png. To think otherwise is to fetishise suffering and limitation.

Now that I have seen this tendency to view the world as a collection of things, I am finding it everywhere. Bureaucracy, ‘content’, managed forests, the value given to metrics, individualism, rationally glib solutions to our ills which disregard the context, spreadsheet brain the lot of it.

There are no solutions as such. But immersing ourselves in creating quality, in appreciating life in the moment, becoming less goal-oriented, all of these will help. We don’t have to stop using our tools. We just have to remember who we are, our indefinable quality of humanness.